In late 2016, Ida Auken, a member of the Danish Parliament, penned an article for an organization called the World Economic Forum (WEF). The title of her piece was “Welcome To 2030: I Own Nothing, Have No Privacy And Life Has Never Been Better.”

Auken’s piece was part of a series of articles that the WEF published in November of that year. Each one speculated about what life might look like in 2030, delivering predictions, plans, and (occasionally) warnings.

Most of these articles received virtually no attention, which wasn’t particularly surprising. The WEF publishes a lot of pieces—there are nearly 50,000 on their site as of February 2023, far too many for any one article to have much hope of standing out from the crowd. When Auken wrote hers, there was no reason to think it was headed for anything other than obscurity.

But it never pays to assume. As it happened, her article was destined to become one of the most significant political think pieces of the decade. Unfortunately for Auken, the attention it received wasn’t what she’d been hoping for.

This is the story of how a short article by a minor European politician mutated into a rallying cry for the alt-right—and became a PR disaster for a major international foundation.

Table of Contents

Visions of the Future, Brought to You by the World Economic Forum

It’s possible you’ve read a quote from Auken’s article, whether or not you know it. However, you’ve probably never read the piece itself, not least because it’s been removed from the WEF’s site, although you can still find it on the Internet Archive and on Forbes.

Like it or hate it, it’s worth a read. That’s more than you can say for most of its sister pieces, which feature sentences like “there is a working hypothesis in many humanitarian organizations that we do not fully understand yet what the impact of technology will be.”

Riveting, right? In contrast, Auken’s article is a breezily told story.

It describes the day-to-day routine of a citizen of a futuristic city where the concept of personal property has become obsolete. According to the unnamed narrator, “I don’t own anything. I don’t own a car … a house … appliances or any clothes … everything you considered a product has now become a service … one by one all these things became free, so it ended up not making sense for us to own much.”

In Auken’s imagined city, life is automated, with “AI and robots” taking care of everyone’s needs. The principal virtue seems to be environmental sustainability. Concrete has been swapped out for greenery, and privately owned cars have been replaced by “driverless vehicles” and bikes.

Life has become largely communal. The narrator doesn’t pay rent because her home is a shared space. When she’s out and about, her living room is used for business meetings.

Privacy, too, has become a thing of the past. There’s nowhere the narrator can go to escape the unblinking eye of the city’s cameras—the only thing that she expresses any discontent with. “Everything I do, think and dream of is recorded. I just hope that nobody will use it against me.”

Depending on your perspective, Auken’s vision of the future might be seductive, with the narrator’s sacrifices seeming more than justified by the harmonious lifestyle she enjoys. Or it might be terrifying, a haunting depiction of a dystopia that could be just around the corner.

Initial Reception

When the WEF published Auken’s essay, it was greeted by a resounding silence. There’s no reason to believe that more than a handful of people read it. It was just one more drop in the vast sea that was the political blogosphere, interesting but ultimately ignorable.

In February 2017, the WEF posted a video, “8 predictions for the world in 2030.” Their first prediction was a reference to Auken’s article. “You’ll own nothing and you’ll be happy. Whatever you want, you’ll rent, and it’ll be delivered by drone.”

It’s tempting to say the video gave Auken’s piece a new lease on life, but it didn’t. The WEF’s video attracted a modest amount of attention, but it didn’t take the world by storm.

Three years passed. Then, in early 2020, there was an outbreak of a new respiratory disease in Wuhan, China. Before long, it spilled out of its city of origin, and the world promptly lost its mind.

You know what happened next. Entire countries went into lockdown. There was a global market crash. In the span of a few weeks, trillion-dollar industries virtually ceased to exist.

The Great Reset

In June, against this backdrop of economic chaos, the World Economic Forum issued a statement.

The disruptions caused by COVID-19—so it said—had laid bare weaknesses that were already present in our society. These were failings in modern capitalism, a system that had brought unprecedented prosperity to millions of people, but that had also set the world on a path towards ever-increasing inequality and environmental catastrophe.

In the WEF’s view, the pandemic was a disaster, but it was also an opportunity. Inherent in the sudden destruction of the market economy was the chance to rebuild it and get it right this time, to create a new system that was fairer and more sustainable than the old one.

The WEF dubbed their proposal the Great Reset.

The Media’s Reaction

The media’s initial response to this was muted.

Although the WEF issued their statement with gravitas and grandiosity, it wasn’t really all that remarkable. Critiques of consumer capitalism aren’t exactly hard to come by; wander around for 30 minutes on any college campus in the country and you’ll hear a few of them.

What was more, it wasn’t entirely clear what the Great Reset was supposed to be. The WEF’s announcement was long on platitudes and short on details. It was clear that they wanted to promote policies that would lead to a more sustainable future, but beyond that, they were vague.

The most concrete suggestion in the WEF’s initial article was that “governments should implement long-overdue reforms that promote more equitable outcomes … these may include changes to wealth taxes, the withdrawal of fossil-fuel subsidies, and new rules governing intellectual property, trade, and competition.”

That wasn’t nothing, but it also wasn’t much—exactly one rhetorical notch above the “eat the rich” rant you’d have heard on that college campus.

The Great Reset might have been quietly forgotten if not for the sheer star power behind it. Whatever it was, it carried the endorsement of some of the most prominent people in Europe, including Charles III, then Prince of Wales, now King of the United Kingdom. It also had the backing of Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, one of the financial arms of the United Nations. And then, of course, there was the founder and chairman of the WEF itself, a man named Klaus Schwab.

Write down that name. It’ll be important later.

The Great Reset Becomes a Meme

Over the next few months, the WEF released several follow-up articles and even published a book about the Great Reset, pumping out a lot more words without doing much to clarify what it was.

Meanwhile, the pandemic continued to rage. More than half of the world’s population was under some form of lockdown, and this cloistered environment proved to be a breeding ground for conspiracy theories.

Millions of scared, stir-crazy people asked themselves: are we being lied to about COVID-19? Is this pandemic really as serious as they say, or are our governments using it as an excuse to grab more power? And is this virus truly natural, or was it a bioweapon released by the Chinese government or—more outlandishly—by some shadowy cabal for their own ends?

In October 2020, with both the virus and these theories propagating, users on the notorious “Politically Incorrect” discussion board of 4chan.org discovered the Great Reset. They reacted to it with what one might call “healthy skepticism,” if one were euphemistically inclined.

Unlike society at large, they didn’t think there was much mystery about what the Great Reset was. To them, it was clear that it was a brazen plot to implement a globalist-socialist-totalitarian New World Order under a single worldwide government. It’s not clear where they drew this belief from. They seemed to just know.

Their comments displayed the even temper and measured tone that their website is famous for.

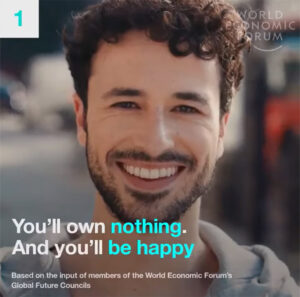

4chan’s users dug up Ida Auken’s article, as well as the “8 predictions” video that had followed it. One user posted a still image taken from the video, a single frame that would soon take on a life of its own.

In the image, a young man beams at the camera. Underneath his angelic smile is the caption, “You’ll own nothing. And you’ll be happy.” The World Economic Forum’s logo is stamped in the corner.

It’s an unfortunate image. Auken’s original article is ambiguous; it’s unclear whether its depiction of the future is meant to be positive, negative, or a mix of both. The frame from the WEF’s video, on the other hand, is frankly alarming. The text feels like a threat. The man’s smile calls to mind Huxley’s Brave New World and a dozen other dystopias in which people are too sedated to notice the hollowness of their lives.

This image and its accompanying phrase spread swiftly, as detailed in a page on KnowYourMeme.com. By mid-2021, millions of people had been told they’d own nothing and like it, and as often happens when slogans go viral, most of the phrase’s original context had been lost.

For one thing, while Auken claimed that her article was meant to describe one possible vision of the future but not necessarily to endorse it, people almost universally took it as a declaration of intent.

The World’s Reaction

Following its rediscovery, the “8 predictions” video saw an avalanche of attention. The comments on it numbered in their thousands. Years later, they’re still accruing at a rate of several per day, and almost all of them are hostile.

“These are not predictions, they are plans,” one Facebook commenter accused recently, with a promise that “your plans will not work.”

The sentiment has been echoed by thousands of others. “We will NEVER comply,” vowed someone else on Twitter.

Nor have the responses been limited to rank-and-file members of the peanut gallery. “You’ll own nothing” has been discussed in parliaments from the Netherlands all the way to Canada. As late as January 2023, Malcolm Roberts, an Australian MP, linked to Auken’s article and called it “inhuman.”

The comments on the WEF’s video have kept coming with no real pause for two years. In that time, Auken has gone from being virtually unknown to being one of Denmark’s most famous (and despised) politicians, all because of an article that, initially, nobody noticed or read.

You Will Eat the Bugs

In an odd twist, people began sending pictures of dead bugs to Auken. Her article had become associated with another memetic conspiracy theory, one which purports that powerful organizations are working to phase out beef and pork in favor of insects, which are cheaper to produce.

If “they” get their way (so the theory goes), soon you won’t be able to walk into the store and buy a hamburger. You’ll have to buy a cricket-and-mealworm patty.

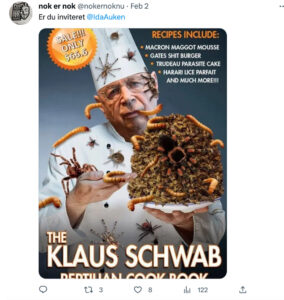

When Auken wrote her article (which contains no reference to bugs), she had no idea that it would one day lead to her receiving an image of a “reptilian cookbook” proudly boasting a recipe for “maggot mousse.” It’s the little surprises that keep life interesting.

Damage Control

Auken tacked a disclaimer onto the beginning and end of her piece, claiming that it was a thought experiment, not a blueprint—a future she saw as possible but not necessarily desirable.

It was a futile gesture. Most people never saw the disclaimer, and many of those who did either flatly disbelieved it or didn’t care.

The WEF eventually took the article down. According to Adran Monck, Head of Communications at the WEF, they did this at Auken’s request, due to the “abuse and threats” she’d received.

Unfortunately for the Auken and the WEF, that wasn’t enough to put the genie back into the bottle. There was no going back; a five-year-old article and a single frame from a video clip had irreversibly damaged their online reputation.

In certain circles, the WEF’s bug-eating, own-nothing agenda has become an established fact. The belief has deep roots, even though most of the people who hold it would struggle to answer the basic question: what even is the World Economic Forum, anyway?

A Five-Minute History of the World Economic Forum

The simple answer to that is that the WEF is a group that organizes a yearly political and economic gathering. As detailed in their online mission statement, “the Forum engages the foremost political, business, cultural and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas.”

That’s a good mission statement. It’s good because it tells you almost nothing and it’s boring beyond belief, which means it will discourage most people from digging around and asking annoying questions.

But let’s pretend you’re not “most people.” You won’t be deterred; you want to know more.

The less-simple answer is that the WEF is the brainchild of a man named Klaus Schwab. Remember him? You were supposed to write down his name. Whether or not you’ve heard of him, you’ve seen him at least once before—on the cover of a fake cookbook, covered with bugs.

Schwab is a German economist. In 1970, when he was a young unknown, he had a vision—a yearly, invitation-only gathering featuring the Western world’s top business leaders.

The intended subject of this meeting was almost comical in its banality: management techniques. Schwab dreamed of introducing the American management style, which he saw as more modern and efficient, to his European colleagues.

He chose to hold his event, initially called the European Management Symposium (EMS), in Davos, a ski resort town in the Swiss Alps.

The Growth of the EMS

In the EMS’s early years, it was as much a party as a business event. Invitees showed up dressed in winter sports regalia and bounced between seminars and the slopes. In the evenings, champagne and cocktails flowed freely.

Unsurprisingly, the event proved popular. It soon outgrew its beginnings as a management symposium and became a forum where its attendees could discuss—well, anything. What do rich and powerful people talk about when you get enough of them in a room together?

Finance, as it turns out. Geopolitics. Trade. Science and technology. Whatever issues they happened to be dealing with that year.

Before long, the invitees included heads of state as well as executives, and eventually even a few religious leaders. In 1977, Franz Cardinal König, the Archbishop of Vienna, attended and “voiced his concerns about humankind’s egotistical drive for material wealth and comforts.” It was one of the first critiques of capitalism to come out of Davos, but not the last, a lecture on wealth delivered in the midst of a gathering of some of the world’s wealthiest people.

By the time the EMS changed its name to the WEF in the mid-80s, it had become one of the world’s most important deal-brokering events. If you were a CEO or politician looking to network or negotiate with one of your counterparts, there was a good chance you would see them at Davos.

The WEF sprouted additional limbs. Its single yearly symposium turned into four, although the Davos event remained by far the most important. It launched a bewildering array of initiatives and started advocating for its favorite -ities, -isms and -tions. Diversity. Equity. Environmentalism. Education. International cooperation. Globalism.

Before long, the Forum had made the transition from a simple yearly meeting to a complex network of philanthropic and lobbying groups.

How Powerful Is the WEF, Really?

So that’s the WEF’s history. A logical follow-up question is, how much power does it have? Does it merit the conspiracy theories it’s attracted?

The answer is that the World Economic Forum has very little actual power—on paper, anyway. At its core, it’s just a private nonprofit that arranges an annual meeting and lobbies for its favorite causes. There are hundreds of organizations like it.

But the Forum is undoubtedly influential. It regularly hosts some of the world’s richest businessmen and most powerful politicians, and when they attend, they’re exposed to its agenda.

And that agenda is still largely set by one man: Klaus Schwab.

The Enigmatic Klaus Schwab

Schwab is something of a contradiction. He’s fabulously well-connected—and nearly invisible. For more than fifty years he’s rubbed shoulders with some of the world’s most powerful people, but although “Davos” has become a household name, Klaus Schwab has not.

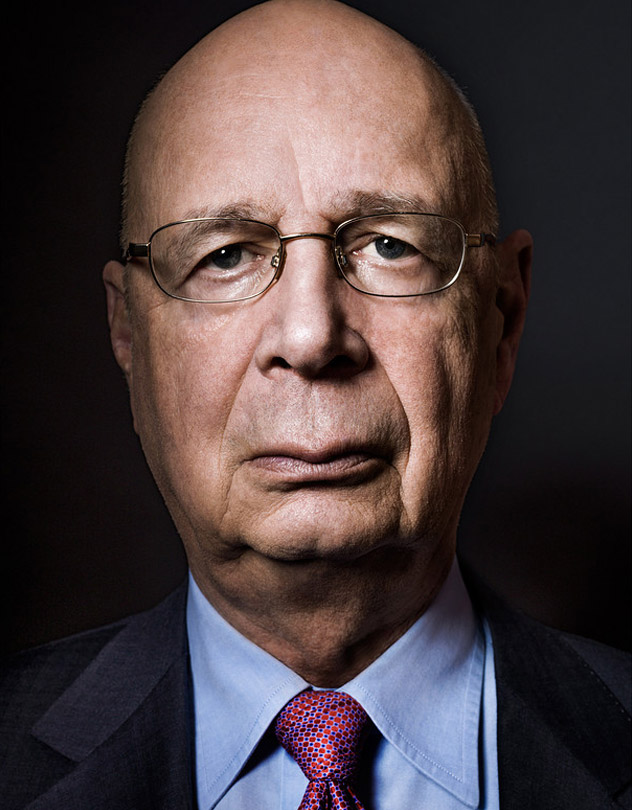

In contrast to many of the businessmen who’ve attended his meetings (they have, by the way, mostly been men), Schwab doesn’t have a big personality. A morose-looking man with a deep voice and ponderous manner, he seems most comfortable speaking and writing in the loquacious, jargon-heavy style peculiar to managers the world over.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Schwab described himself as a “very unsocial person.” It may be this lack of sociability that’s made him a focus for conspiracists. When you reveal very little about yourself, other people are free to use you as a canvas and project what they expect to see.

Whatever the reason, millions of people deeply distrust him. Schwab isn’t public enemy number one for the populist right—that honor goes to George Soros—but he might be public enemy number two (it’s either him or Bill Gates). If you ask four different people what Schwab’s agenda is, you’ll get four different answers, but odds are, at least three of them will involve bugs.

The Dour Face of a Conspiracy

Schwab’s WSJ interview features a photo. It’s been endlessly reproduced and shared, often with comically over-the-top edits. Sometimes Schwab is looming monolithically over a globe. Sometimes he has devil horns or red eyes.

Like the infamous still from the WEF’s “8 predictions” video, the composition of the photo is unfortunate. The lighting on Schwab’s face is dramatic and ominous. His expression is grim, his eyes cold. He looks like he really could be the head of a conspiracy to tear down and remake society—a sinister puppetmaster hiding in plain sight.

Or maybe he doesn’t. Maybe he looks like an ordinary, slightly tired old man. Maybe people see what they expect to see.

Is the Great Reset Conspiracy Theory True?

At this point, I’m going to write something that about eighty percent of you have already guessed and that twenty percent of you will be completely alienated by: the World Economic Forum isn’t actually trying to bring about the New World Order.

They’re not trying to abolish private property or depopulate the planet with COVID-19 vaccines (which people have also claimed). They’re not necessarily opposed to you eating bugs (more on that below), but they’re certainly not going to force you.

There’s just no actual evidence for any of the wild claims about the Great Reset. Or rather, the “evidence” is all retroactive. The proponents of the conspiracy theory didn’t follow a trail to its inevitable conclusion. A few people on 4chan drew a wild conclusion first and then the internet engaged in a bit of collective mythmaking, finding ways to justify it after the fact.

Take Ida Auken’s article, which sparked the whole thing. In people’s heads, “you’ll own nothing” has become inextricably tied to the Great Reset, a sign of what it’s really all about—but Auken’s article predated the Great Reset by more than four years.

Sometimes, this sort of thing just happens. In the 1980s, thousands of people believed in an epidemic of Satanic ritual abuse with about as much justification.

Are you still with me, or have I lost you?

Still there? Cool.

Now that that’s out of the way, it’s worth examining the Great Reset in more detail. Because, although it’s not as sinister as some have claimed, it’s not necessarily completely benign, and in some ways, it’s the WEF’s own fault that it became the subject of a conspiracy theory.

Why the Great Reset Is Perfect Conspiracy Theory Fodder

The Great Reset’s most notable quality may be its own sheer vagueness. The WEF has poured enormous resources into promoting the Great Reset, and yet even today, nobody can really explain what it is.

Take Schwab’s book on the Great Reset. Here’s an excerpt from it, on a path toward a more sustainable version of capitalism:

“The green economy spans a range of possibilities from greener energy to ecotourism to the circular economy. For example, shifting from the ‘take-make-dispose’ approach to production and consumption to a model that is ‘restorative and regenerative by design’ can preserve resources and minimize waste by using a product again when it reaches the end of its useful life, thus creating further value that can in turn generate economic benefits by contributing to innovation, job creation and, ultimately, growth.”

Did you read that? Did you retain any of it?

Come on, be honest. Of course you didn’t, and good for you; it’s nearly unreadable.

Here’s what that paragraph boils down to: companies should make their products reusable, or, more pithily, waste not, want not.

Almost all of the material that the WEF has published on the Great Reset is like that, shallow analyses and banal suggestions written out with about five times the words they need.

None of this seems to justify the time and energy that the WEF has spent on promoting the Great Reset. It’s arguably not surprising that many people—not all of them conspiracists—have reacted with some form of “This can’t be all there is.”

It’s hard to see the WEF’s vagueness as anything other than a serious mistake. The murkiness of the Great Reset turns it into another blank canvas. And it makes it very hard to “disprove” the conspiracy theories. You can point out that there’s no evidence for what people are saying about the Great Reset, but it’s difficult to explain what it actually is instead.

The WEF’s Impeccable Communication Skills

Further muddying the waters are the thousands of articles the WEF has published on their website—articles like Ida Auken’s.

Proponents of the Great Reset conspiracy theory argue that these articles hint at Klaus Schwab’s “real” agenda. And it must be said that they don’t do very much to engender trust. Many of the articles are more than a bit creepy.

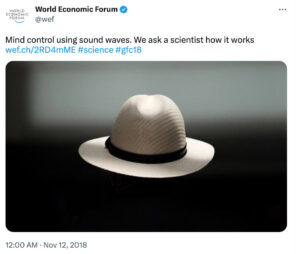

For instance, there’s this one, in which the WEF discusses “mind control using sound waves.”

Now, if you click into that article, you’ll see that at no point does the WEF say that it, itself, actually wants to control your mind with sound waves. In fact, the article is about the need to use the technology responsibly. But still, their tweet is a bit … off, isn’t it?

There are dozens of examples like this, instances where the WEF seems to veer out of their way to say something dystopian. It’s a weird habit.

If you want people to trust you, it probably isn’t the best idea to publish the words, “For example, should you implant a tracking chip in your child? There are solid, rational reasons for it, like safety.”

You also probably shouldn’t extoll the virtues of eating bugs beneath a huge banner labeled “The Davos Agenda.”

What, you thought that part was made up? Just a nutty internet thing? Well, it’s true that Ida Auken never said you should eat bugs, and neither did Klaus Schwab, but someone else sure did, and the WEF published it for them.

WEF Truthers would say that these are glimpses of the organization’s “true” agenda. But there’s another possibility, a more realistic one—that the Forum just has a shockingly incompetent public relations team.

Mainstream Criticism of the World Economic Forum

There’s one final factor that’s made the WEF into a lightning rod for conspiracists: the organization’s spotty track record when it comes to ethics and transparency. Although the Forum’s ideals sound lofty, they haven’t always met them.

What follows is a brief and by no means exhaustive summary of some of the WEF’s past controversies:

Environmental Hypocrisy

The WEF has repeatedly drawn fire from environmentalists, which is surprising given how much they talk about sustainability. Greenpeace has repeatedly protested against the huge carbon footprint of each meeting in Davos.

They have a point. In 2020, The Guardian pointed out the hypocrisy of Prince Charles calling for tighter environmental regulations at Davos after being deposited there by his private jet.

Nor is he an anomaly. In 2023, more than 1,000 private jets flew in and out of Davos for the meeting (one of the designated themes of which was “climate change”).

Financial Transparency

The WEF receives hundreds of millions of dollars per year and operates as a charitable foundation, which means it pays no federal taxes under Swiss law. No one is sure where all of its money goes, but historically, Schwab has used some of it to fund his own pet projects, which have included for-profit ventures with no relationship to the WEF’s goals.

Klaus Schwab himself draws a salary of around $1,000,000 USD per year. He also reportedly dips into a sizable expense account when hosting guests or traveling.

According to the book Davos Man by Peter S. Goodman (an excerpt of which was republished in Vanity Fair), the WEF has spent more than $80 million USD purchasing land in Switzerland, “including two parcels bridging Schwab’s home and the Forum headquarters, making them contiguous.” (This refers to the WEF’s official HQ in Cologny, Switzerland, not in Davos.)

Performative Activism

None of this is wholly damning. If you’re looking for a smoking gun proving that Schwab is trying to get you to own nothing and be happy, you won’t find it here.

But what you will find still isn’t great.

Looking at it all, a picture starts to emerge. It’s not of an Illuminati-like cabal but of something more mundane, a group of ultra-rich people behaving in the way that ultra-rich people usually do. Klaus Schwab and his cohort make a lot of noise about equity and sustainability, but when you look at their track record, it’s hard to shake the feeling that it’s all somewhat performative.

The vagueness of the Great Reset might not be a bug but a feature. If Schwab was any more definite, his proposed solutions might require him and his friends to commit to making actual sacrifices.

Everybody Tighten Your Belts (But Just You Guys, Not Us)

There’s a larger issue inflaming the backlash against the WEF’s Great Reset agenda: they’re just not the kind of organization that people want to deliver messages about wealth and finance.

After all, at its core, the WEF is an exclusive gathering for the rich and powerful. Executives. Celebrities. Royalty. Politicians. One-percenters. It’s never pretended to be anything else.

When people like that start talking about the need for economic reform, it’s easy to get cynical and defensive, as shown by hundreds of comments on Schwab’s speeches on Facebook and YouTube.

The rhetoric might be exaggerated, but this response isn’t necessarily irrational. After all, corporations love to talk a big game about progressive causes and then pass the costs on to the consumer.

Consider the plastics industry, which has spent untold millions on ads hounding you to recycle while doing very little to curb its own environmental impact. Or consider restaurants, which are always badgering you to tip more while paying their servers under minimum wage.

Nobody likes being lectured on the evils of consumerism by the people who’ve benefited from it the most.

It’s reminiscent of John Lennon’s song “Imagine,” which might as well provide the musical accompaniment to Ida Auken’s “you’ll own nothing” article. “Imagine no possessions,” Lennon crooned in 1971, the same year that Klaus Schwab arranged the first meeting of the EMS. Infamously, at the time, Lennon had an entire room in his apartment dedicated to refrigerating Yoko Ono’s fur coats.

It’s a Party and You’re Not Invited

In a way, it would almost be comforting if the WEF did have a sinister agenda. It’d be nice to imagine that you’ve never gotten an invitation to Davos because its attendees are conspiring against you—but what if it’s just because they don’t care about you? The reality is more mundane than the conspiracy, but somehow more galling.

If the WEF is bad at public relations—and it is—maybe it isn’t because they’re plotting something cartoonishly evil. Maybe it’s because they don’t talk to people outside of their club and have a tough time predicting how they’ll react to topics like bug-eating and mind control via sound waves.

The World Economic Forum is the perfect villain for the internet age. The paradox of the internet is that, for the first time in human history, we all have the freedom and power to say whatever we want, and yet collectively, we’ve never felt less heard. On the contrary, the gap between the movers and shakers and those who get moved and shaken has never felt wider.

In this environment, maybe it isn’t surprising that a highly exclusive club like the World Economic Forum ended up being the subject of conspiracy theories. Maybe the surprise is that it took so long.